Written by Malvyne Rolli-Derkinderen, MD, a specialist in neuro-gastroenterology. Area of Expertise: Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease, University of Nantes

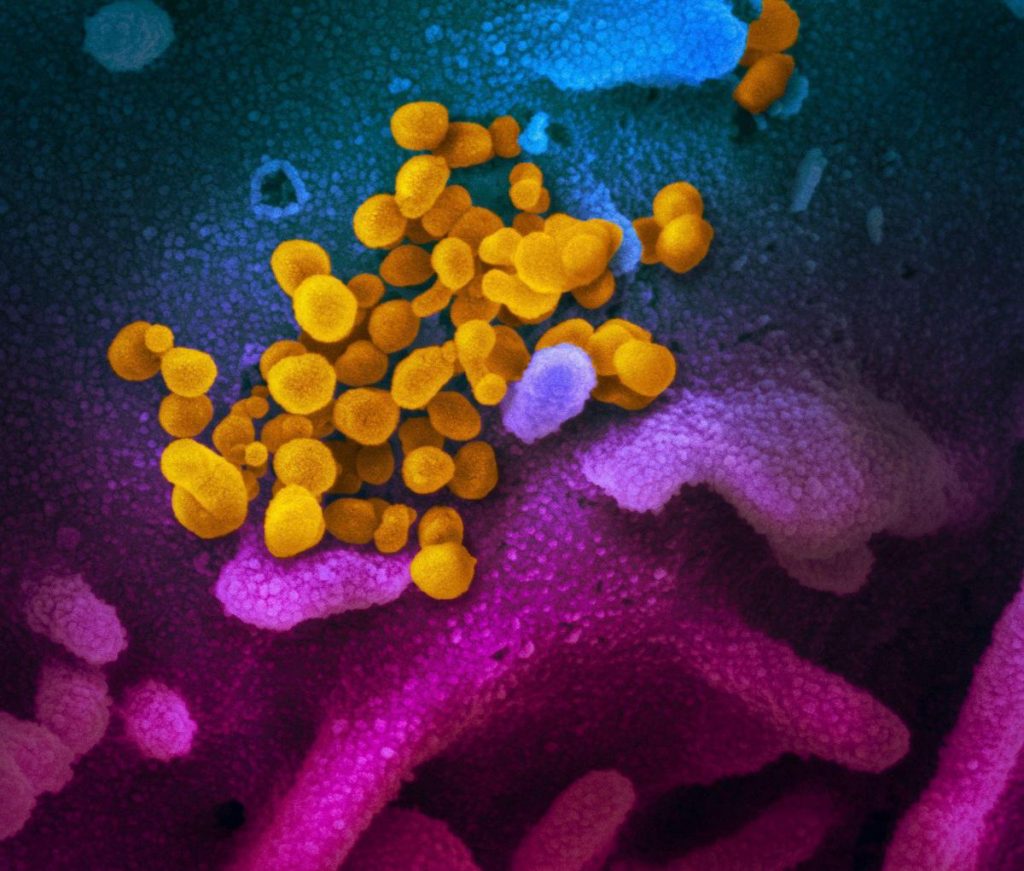

It’s the star of the new science, the gut microbiota. This complex group of microorganisms, viruses, fungi and other bacteria can be the origin of many diseases.

This article originally appeared Conversation.

This article was published as part of the Fête de la science, which starts at 1 Until October 11, 2021 in mainland France and from November 5 to 22, 2021 abroad and internationally, of which The Conversation France is a partner. The theme of this release is: “Eureka! The passion of discovery.” Find all the events in your area on the Fe . websitetedelascience.fr.

In recent years, the laboratory star that has made its way into the general public … the intestinal microflora, as it revolves around it, is seen to be embellished with many virtues if not interesting and not always useful forces: both in the context of purely gastro-intestinal diseases and neurological diseases Or psychological, it is now considered a full-fledged player in the development of certain diseases.

In addition, it is easily accessible, and it seems that it can be easily analyzed or modified, scientists ask themselves the following question: if it can cause diseases, can it also help to treat them or even prevent their appearance? To what extent can we use it to improve our health?

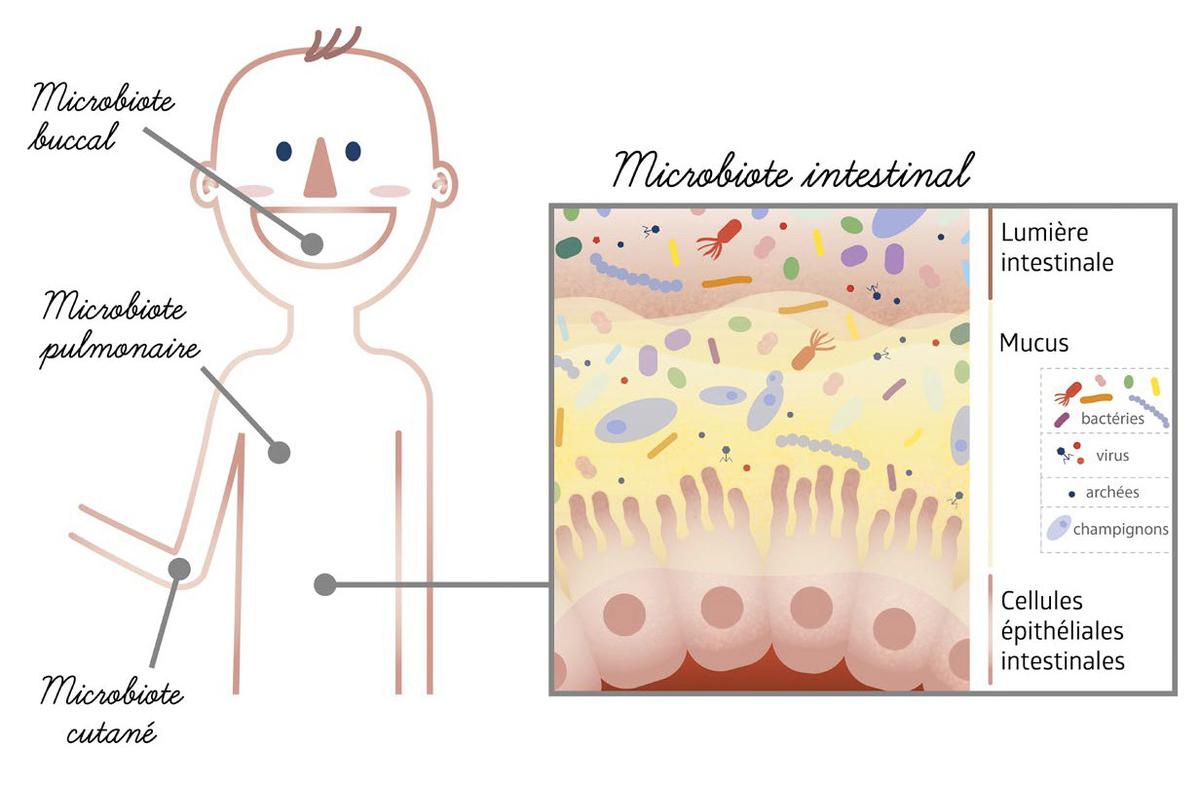

To answer, we must briefly redefine what microbes are: each complex, made up of a great variety of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea. Microorganisms are also incorporated into an ecosystem: thus there can be as many microorganisms as ecosystems … hence the need to outline them. And remember that each of our organs that come into contact with an external environment (not just the intestines) has its own microbiome – skin, mouth, lungs, etc. Together, they make up the human microbiome.

Julie Burgess / Inserm Mibiogate

The importance of these microorganisms is partly due to the fact that microorganisms develop in a strategic place: at the edge of our organs, where they form a buffer zone between the internal environment and the external environment. Through their interaction with our cells, they are able to quench variations in these environments and often represent the first means of excluding pathogens. The gut microbiota interacts, for example, with the outer cells (or epithelial barrier) of the gut, the immune system, and the enteric nervous system (the part of the autonomic nervous system that controls the digestive system).

Our bodies provide them with a place to live in exchange for helpful assistance in many cases. But the imbalance will contribute or may be a cause of the development of chronic diseases. While it may seem easy to restore balance by correcting the germs involved, let’s not forget the influence of other scales in balance: the host and the external environment.

Weighing gut bacteria on our health

The gut microbiome It contains 10 bacteria and 100 times more genes than the entire human genome. It plays an essential role in the development of the immune system, nervous system, and metabolism of its host.

A species of bacteria, belonging to five major phyla (Bacteria, persistence, actinomycetes, proteobacteria And verrucomicrobe), constituting healthy human faecal microbes. Its composition is essential for maintaining intestinal homeostasis and reflects, to a varying extent, the general health of the host.

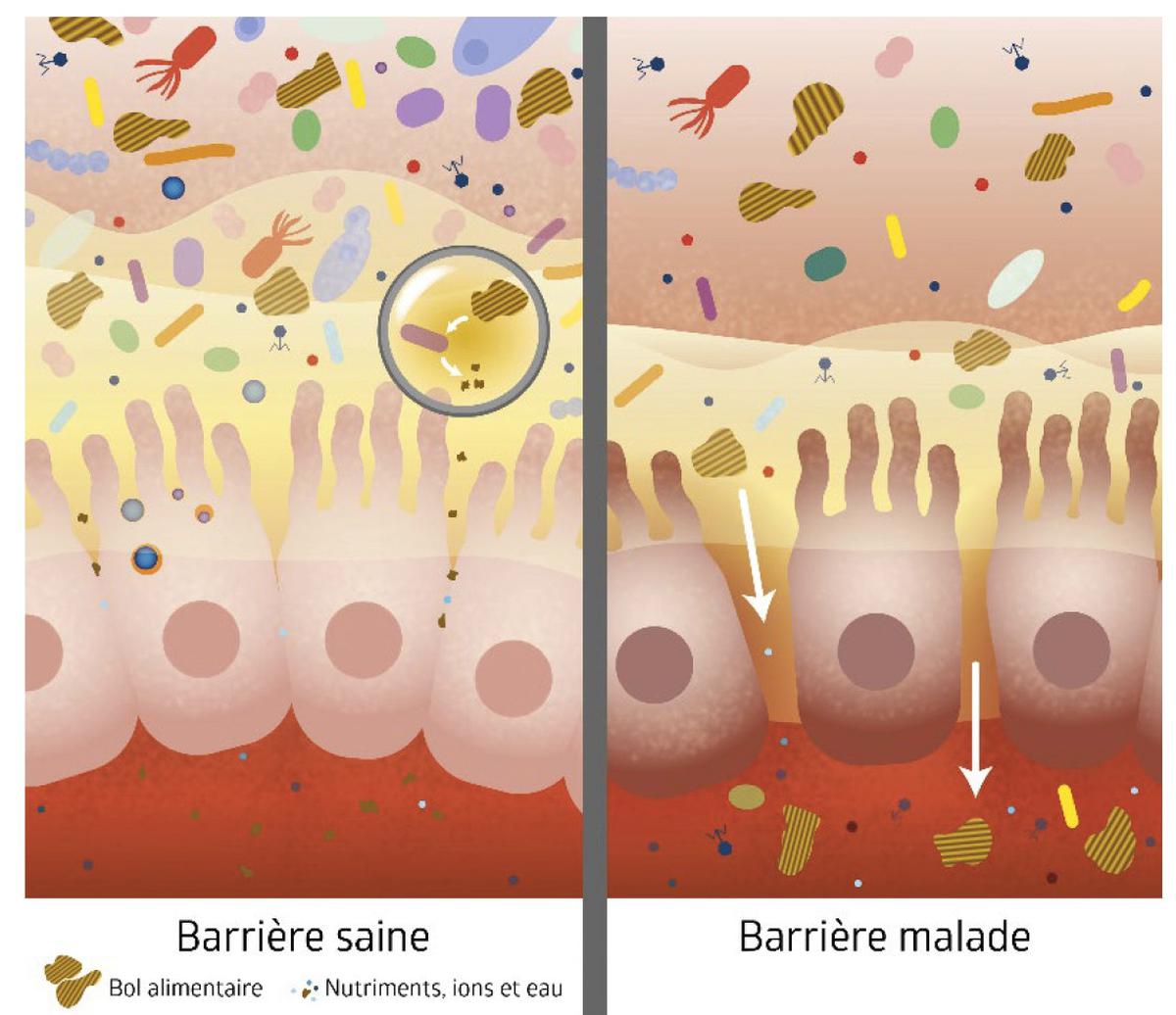

A group of researchers from the Loire region focused their research on the regulation of organ barriers where germs settle and their relationships ( MiBiogate Project). If these barriers were not airtight, they would be crossed in a highly controlled manner in healthy individuals. In our intestines, it is the layer of cells of the digestive epithelium that forms this porous barrier in one form or another. Its permeability is regulated according to its specific condition as well as the state of the intestinal flora, immune system and enteric nervous system.

Dysfunctions have been observed in several gastrointestinal diseases (chronic inflammatory bowel disease) or additional gastrointestinal diseases (type 2 diabetes, obesity, autism spectrum disorders, and Parkinson’s disease). However, these same diseases are associated with “dysbiosis”: a change in the composition and functions of the intestinal microflora.

So many studies seek to determine to what extent, by improving our microbiota, we can strengthen our barrier, and thus our health.

Julie Burgess / Inserm Mibiogate

Basic Interactions

In 2013, the first studies indicated dysplasia in the genesis of diseases such asobesity or the Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, by showing that transplanting microbes from a diseased mouse into a healthy mouse will lead to the development of diseased characters.

On the contrary, the New England Journal of Medicine Study reports show that transplanting healthy stools is effective, in the vast majority of cases, in treating bacterial infections Clostridium difficile. These bacteria develop after the germs have been exhausted, often after treatment with antibiotics, and cause severe diarrhea, inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Roughly 14,000 Americans die from it every year.

Since then, several studies have sought to understand host-microbial interactions. Thus, the Mibiogate Consortium brings together the expertise and tools of professionals. This enabled him, for example, to notice that vesicles of bacteria can contribute to exacerbation of metabolic diseases, Such as Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease Which can develop into cirrhosis.

With five thesis projects, the Mibiogate Consortium is expanding its perspective and its field of research. studying now Bacterial barrier interactions of different organs Thanks, in particular, for developing bioinformatics tools and Applications. Tools that open the door to a still unexplored section of knowledge relating to these interactions.

Research to control our germs

In addition toStudy their interactionsMibiogate addresses the “how?” questions. And when? » Intervention to improve or restore it effectively.

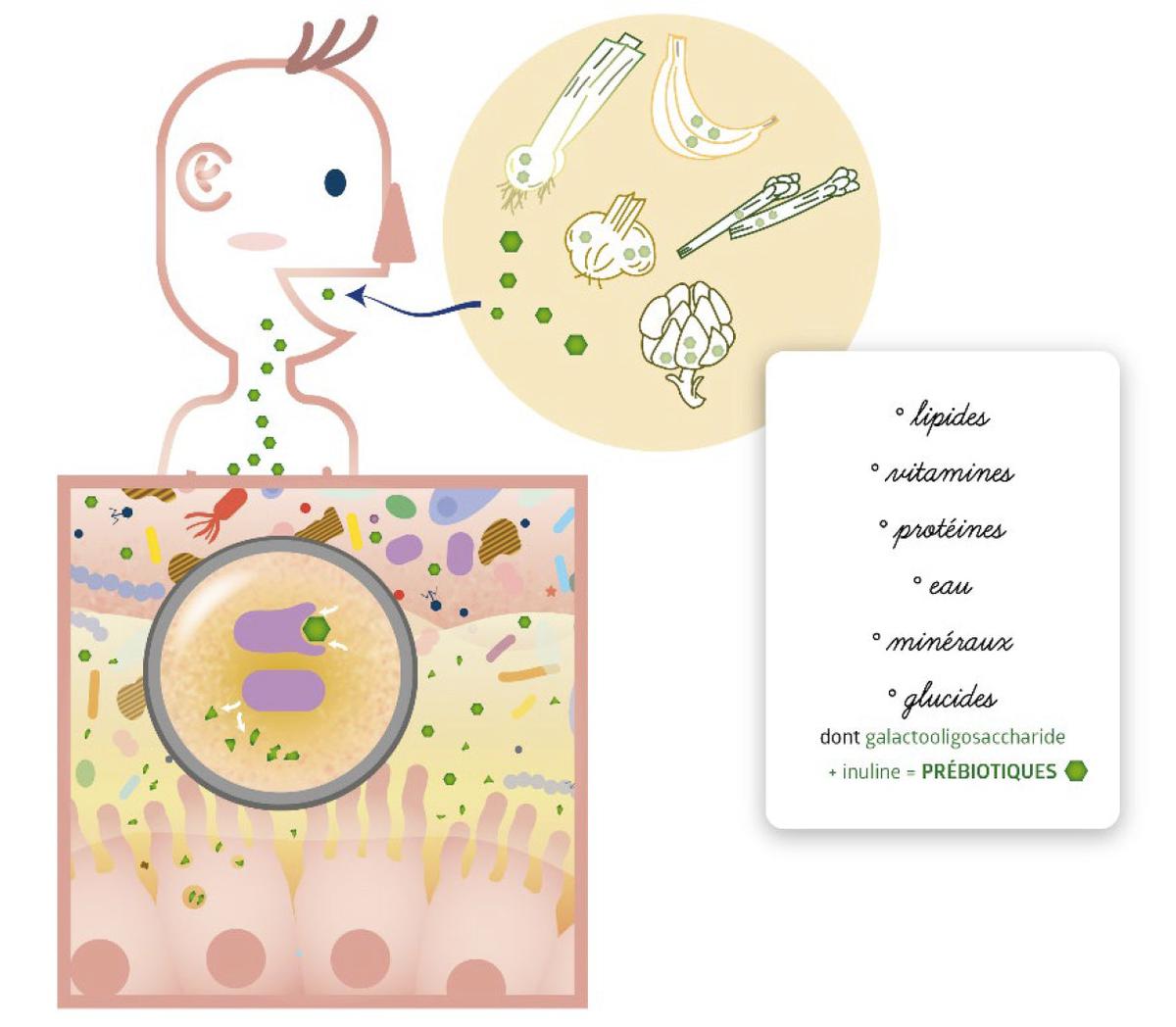

Regarding the “how” already. Various strategies exist to modify or control microorganisms : Through food, prebiotics, or probiotic cocktails. In addition to these direct methods, we must take into account our state of stress, the quality of our sleep and our physical activity, then by changing the activity of the fermenter we are, we will modify our microorganisms. These global enrichment strategies are supplemented with bacteriostatic, postbiotic products, which should have higher efficiency and more targeting, but all of this is still being studied.

Julie Burgess / Inserm Mibiogate

As for ‘when’: Determining the origin of the development of chronic diseases in order to understand why, how and when they can be seized is one of the most important lines of current research. By characterizing the time windows that determine the composition and activity of the intestinal microbiota, the goal is to be able to offer tailored therapeutic solutions and preventive strategies in particular.

Our hypothesis would be that a defect in its proper establishment could underlie the development of future diseases. In fact, the onset of chronic diseases takes a long time, and often patients do not have symptoms for several years: we can assume that they have an early origin, From the embryo stage. It is the concept of the developmental origin of health and disease (Doha).

Much research tends to show that there is a link between exposure to environmental factors during the first 1,000 days of life (from conception to two years of life) and the occurrence of chronic disease. In particular, this research indicates that the components of the host’s microbiota can then be modified, the immune system and metabolism, and interact differently to protect or cause the development of these diseases in adulthood. This is when it is necessary to work to establish the formations of spores in a permanent way.

In adulthood, we observe the resilience of the intestinal microflora when it is able to establish itself correctly: if it can be modified by an environmental factor (stress, diet, tobacco, physical activity, pollution, antibiotics, etc.), it regains its initial signature , characteristic of its host, shortly after removing the irritating environmental factor.

As you understand, adopting the right strategy to modify the microbiota and avoid catching a chronic disease is still in its infancy. However, a common feature in many studies is that the poverty of our microbiota is associated with different disease states, while their richness and diversity reflect the organism’s resistance and healthy character. Let’s grow our microbes!

The project MyBiojet was wearing it By Michelle Neulist, DirectorUMR1235 Karen Gimbert, Mibiogate (Inserm) Project Manager and Science Moderator, co-designed and wrote this article. Éléonore Dijoux, Amélie Lê, Aurélie Loussouarn, Alexandre Villard and Johanna Zoppi contributed this scientific knowledge by implementing their thesis within the Mibiogate project.

“Music guru. Incurable web practitioner. Thinker. Lifelong zombie junkie. Tv buff. Typical organizer. Evil beer scholar.”

More Stories

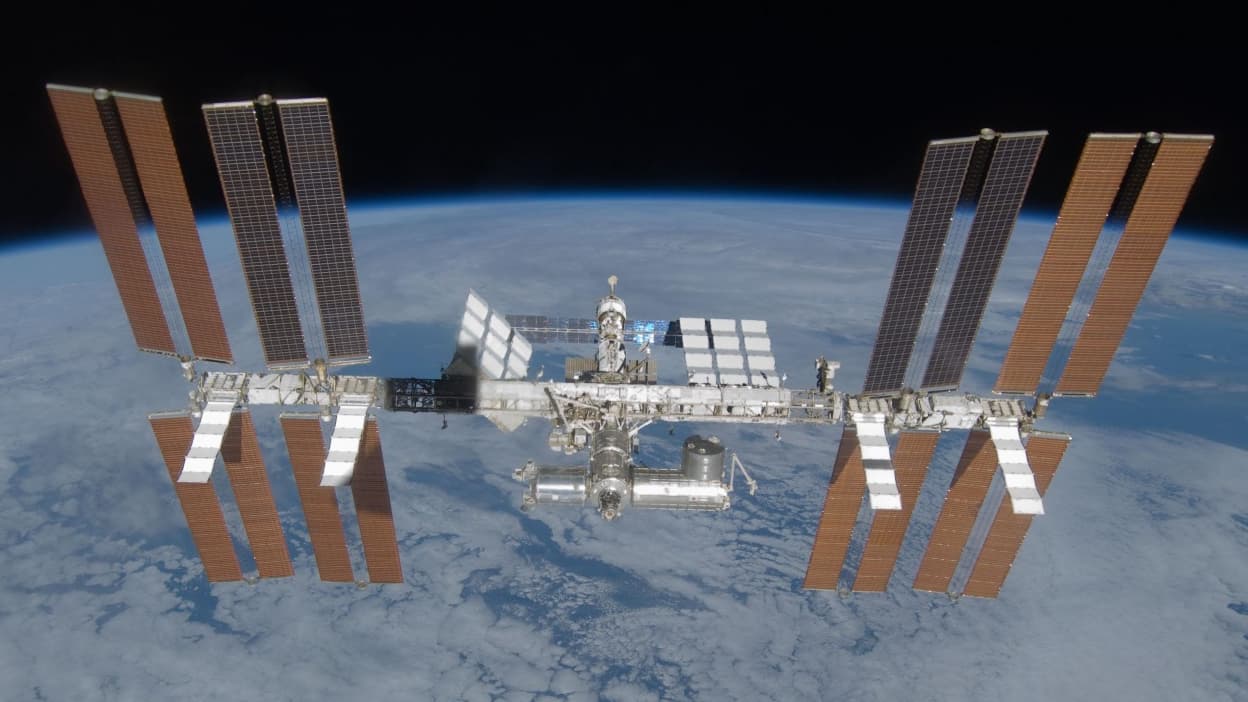

Bacteria brought into space mutated and became stronger on board the International Space Station, study finds

Sperm for science used in fertilization: already 16 contacts

Scientists have discovered new health risks associated with microplastics