A study published on Wednesday (2) in the scientific journal natureAn international team of researchers has produced unprecedented information about the way of life of a group of people who lived in China 40,000 years ago.

Excavations carried out at the archaeological site of Ciamabe, in the Nihuan Basin, in the north of the country, have revealed an ancient factory of “ocher”, a natural clay pigment, shedding new light on the processes of innovation and culture. The diversification that occurred in East Asia during the period of genetic and technological mixing.

To date, very little is known about the life and cultural adaptations of early Asian peoples at this point. In the search for answers, the Nihiwan Basin, which contains a wealth of archaeological sites ranging from 2 million to 10 thousand years in existence, is one of the best opportunities for understanding the evolution of cultural behaviors in the region.

The discovery brings new insights into the cultural innovation and expansion of Homo sapiens in China

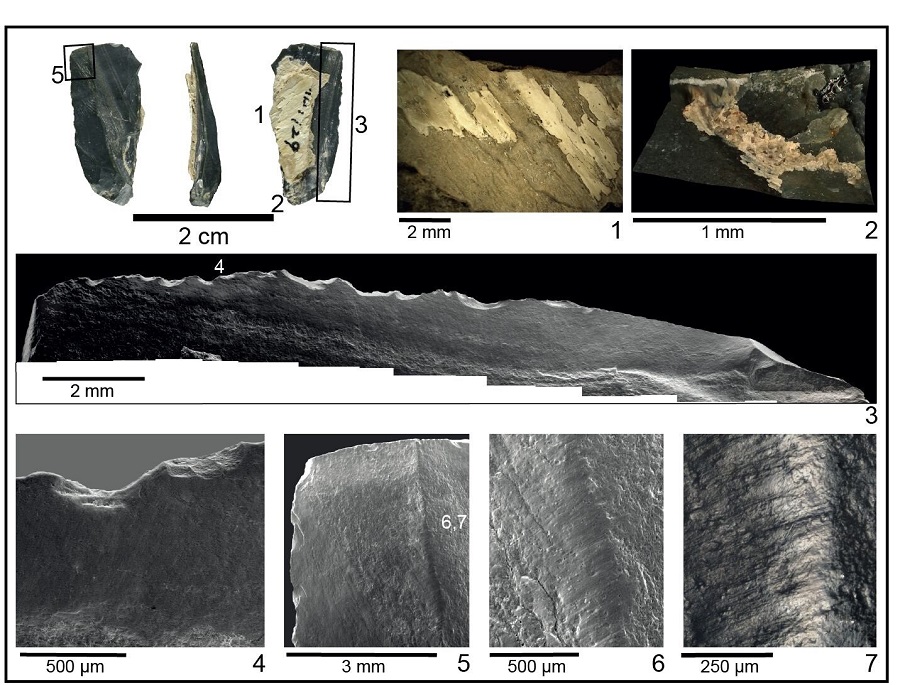

It is the oldest known evidence of ocher processing in East Asia, due in large part to a distinct set of blade-like stone tools unlike anything we see there.

Analysis of the results provides important new insights into cultural innovation while expanding Homo sapiens societies. “Chiamabe is unlike any other known archaeological site in China in that it displays a new set of cultural features from an early history,” said Fa-Gang Wang, a researcher at the China Regional Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology. authors. from the new study.

“Humans’ ability to live in northern latitudes, with very cold and seasonal environments, was likely facilitated by cultural evolution in the form of economic, social and symbolic adaptations,” said Xixia Yang, a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. and a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. Ciampi’s findings help us understand these modifications and their potential role in human migration. »

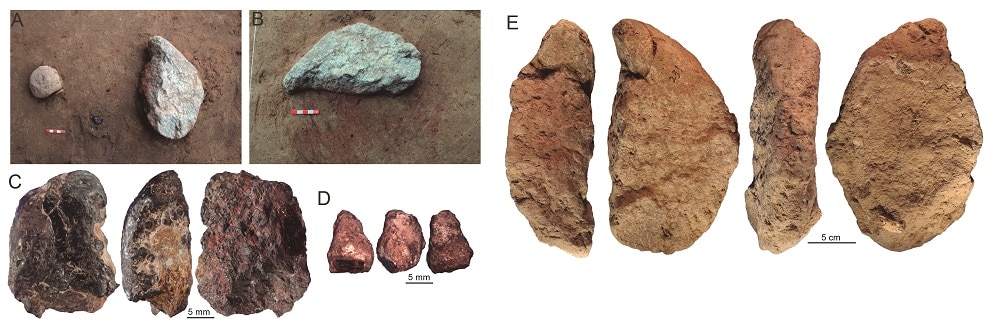

The widespread use of ocher is one of the most important cultural characteristics found in Ciamabe, as evidenced by artifacts found by researchers that were used to process large quantities of pigment.

Among the finds are the remains of two types of ocher with different mineral compositions and a long limestone slab with smooth areas containing ocher stripes, all on a red-stained sedimentary surface.

Analysis by researchers from Purdue University, led by Professor Francesco Derico, indicates that different types of pigments were processed on site, by beating and scraping, to produce powders of different colors and consistency. The production of ocher at Ciampi represents the oldest known example of this practice in East Asia.

More than half of the blade-like stone tools found at Ciamabe, unique to the region, are less than 20 mm thick. Functional and residue analyzes indicate that tools have been used to pierce and scrape leather, sculpt fixtures, and even cut animals, demonstrating a complex technical system for processing raw materials not previously seen at ancient or slightly newer sites.

The diverse stone technology and the presence of some innovations (such as the use of tools carved in stone rather than bone) may reflect an early attempt at colonization by modern humans. This period of colonization may have involved genetic and cultural exchange with ancient groups such as the Denisovans, before it was replaced by later waves of Homo sapiens using microblade techniques.

Modern humans emerged from periodic genetic and social exchanges

For the article’s authors, the archaeological record is inconsistent with the idea of continued cultural innovation, or the whole set of adaptations that allowed early humans to expand beyond Africa and into the world. Instead, researchers believe, one should expect to find a mixture of patterns of innovation, with the spread of previous technologies, the persistence of local traditions, and the local invention of new practices, all occurring in transition.

“Our results show that the current evolutionary scenarios are very simple,” says Professor Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute. And this modern man, and our culture, arose through repeated but different episodes of genetic and social exchange over wide geographical areas, rather than by one rapid wave of spreading through Asia. »

Have you seen our new videos on Youtube? Subscribe to our channel!

“Music guru. Incurable web practitioner. Thinker. Lifelong zombie junkie. Tv buff. Typical organizer. Evil beer scholar.”

More Stories

The Air and Space Forces want a “modular” plane to replace the Alphajet

Spain confirms that it is holding talks with Morocco

The thickness of the ice crust in Europe will be 20 kilometers